Loiasis is a parasitic disease caused by the Loa loa worm, transmitted between humans by deerflies. It affects about 15 million people in Central Africa. The adult worms, which can live for up to 20 years, release millions of larvae (microfilariae) into the bloodstream. In some individuals, these levels can become extremely high, sometimes exceeding 100,000 microfilariae per milliliter of blood.

Traditionally, loiasis was considered relatively mild, causing itching, eye worm migration, or temporary swellings known as “Calabar swellings.” However, recent studies have shown that people with high microfilarial levels may face serious health risks, including a shorter life expectancy. The higher the parasite load, the greater the risk of death.

New research also links loiasis to cardiovascular and kidney complications. Reports over several decades have documented kidney problems such as protein in the urine, nephrotic syndrome, and even kidney failure. Biopsies from affected patients revealed damage such as glomerulopathy and inflammation, with some cases improving after antifilarial treatment.

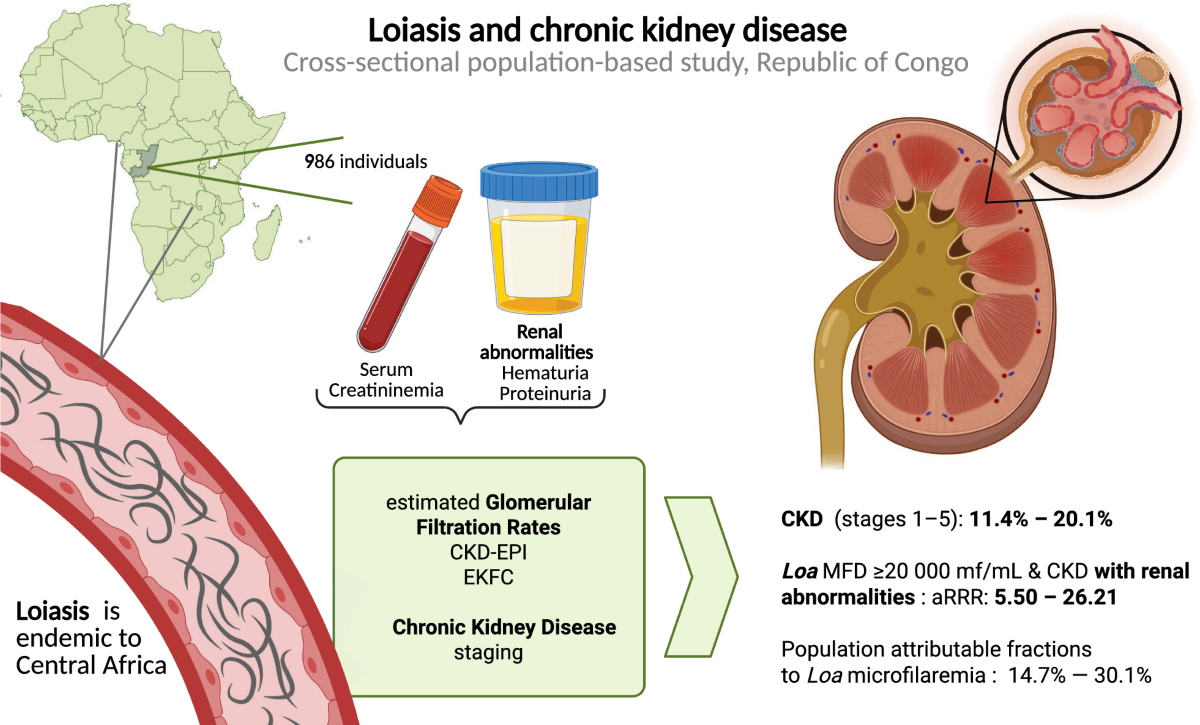

More recently, a large study in the Republic of Congo found a strong link between parasite load and kidney damage, particularly proteinuria (protein in the urine). This was the first large-scale evidence confirming what smaller case studies had suggested for years.

Building on these findings, researchers are now focusing on how Loa loa infection contributes to chronic kidney disease (CKD), highlighting the urgent need for more research and public health attention in affected regions.

Study Area and Population

This cross-sectional study was carried out between May and June 2022 in 21 villages near Sibiti, Republic of Congo. A total of 990 participants, aged 18 to 88 years, were included. All participants had previously been screened for Loa loa microfilaremia in 2021. For this study, individuals who tested positive for microfilariae were matched by sex and age (±5 years) with two individuals from the same village who did not have microfilariae. A detailed description of the study population has been reported in earlier publications.

The sample size of 990 participants was originally calculated to detect whether loiasis increased the risk of malaria and pneumonia. The assumption was that loiasis might impair the spleen’s function, making individuals more vulnerable to infections. However, because there were no prior data, the sample size was not designed specifically to evaluate kidney disease outcomes.

Participation in the study required informed consent from all individuals. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Congolese Foundation for Medical Research and by the National Health Authorities of Congo.

Sociodemographic and Health Data

Information was collected on age, sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and tobacco use. Blood pressure was measured while participants were lying down after a 10-minute rest. High blood pressure (HBP) was classified into three stages, and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was also calculated.

Study Methods and Results

Parasitic infection testing:

Small blood samples were collected to check for Loa loa and Mansonella perstans.

Prior exposure to Onchocerca volvulus was tested with a rapid antibody test, and skin samples were examined if positive.

Urine and stool samples were analyzed for Schistosoma haematobium and soil-transmitted worms.

Malaria was tested through blood films and antibody levels.

Health measurements:

Creatinine levels (to assess kidney function) were measured for nearly all participants.

Blood tests also checked for cholesterol, diabetes (HbA1c), and white blood cell counts.

Arterial stiffness was assessed with a simple pulse test.

Kidney assessment:

Ultrasound scans measured kidney size and looked for abnormalities such as cysts or dilatation.

Morning urine samples were tested for protein and blood using dipsticks. Abnormal results were confirmed under a microscope.

Kidney function was estimated using standard equations (CKD-EPI and EKFC), adjusted for body size.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was classified according to international guidelines.

Key results:

Out of 986 participants tested, 36% had Loa loa microfilaremia.

Other parasites (M. perstans, O. volvulus, S. haematobium, S. mansoni, hookworm) were rare or absent.

Very few had diabetes (1 case) but high cholesterol was common.

Kidney ultrasound showed 109 abnormalities, mostly cysts. Nine people had only one kidney.

CKD prevalence ranged from 13% to 23%, depending on the formula used.

Advanced CKD (stage 3 or higher) was found in 3–8% of participants, but no cases of kidney failure (stage 5).

Factors Linked to CKD Severity

To study how severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) was in participants, researchers used different cutoff points of kidney function (measured as eGFR). Depending on the calculation method, the cutoffs varied slightly, but both showed similar results.

When all possible factors were tested, only a few stood out as being clearly linked to more severe CKD:

Older age → higher risk of severe CKD.

Male sex → more affected than females.

Smoking → strongly linked to worse kidney health.

Arterial stiffness (measured by pulse wave velocity, PWV) → associated with poorer kidney function.

Other factors tested in the models did not show a significant link with CKD severity.

- New research shows that loiasis, a common parasitic infection in Central Africa, can damage kidney function. Scientists suggest the parasite may harm the kidneys after long-term exposure, making it a hidden cause of many unexplained kidney diseases in the region.

No comment